In a couple of previous posts, I examined reasons for moving to a marginal rate system for repaying HELP debt, as proposed by the Universities Accord final report, and what the rates might be.

Under a marginal rate system HELP debtors would repay a % of all income above a threshold amount, instead of a % of all income once a threshold is reached, as now. An advantage of marginal rate repayment systems is that they can reduce effective marginal tax rates. High EMTRs discourage people from taking on more paid work. In some cases under the current system EMTRs exceed 100%, so disposable income goes down despite nominal income going up.

The Accord final report and the minister, Jason Clare, also suggest reducing annual repayments, at least for lower income HELP debtors. Except for HELP debtors just above an income threshold in the current system (especially the first one, where there are very high EMTRs) this is not an inherent feature of marginal rate systems compared to current arrangements. But it could be a political selling point for a marginal rate system designed to reduce repayments.

To cut annual repayments for lower income HELP debtors without causing a major reduction in HELP repayment revenue the government would need to introduce a multi-rate marginal system. This is implied in the Accord final report discussion. Multi-rate systems progressively increase the marginal rate as income goes up. There are many possible sets of rates, but my previous post looks at 7%-17%-22% and 10%-15%-20% models.

This post goes through some of the political implications of moving to a marginal rate system.

How will the percentage numbers be interpreted?

One initial challenge will be convincing people that a 7% or 10% first marginal rate will usually reduce their repayments compared to the current seemingly lower rates. How can charging 7% increase disposable income compared to 1%?!

Of course the answer is what the percentages are of, but for people half paying attention, who have never thought about marginal versus whole of income rates before, a higher percentage rate reducing their repayments is going to seem counter-intuitive.

Getting rid of high effective marginal tax rates

A policy reason for a marginal rate system is to reduce effective marginal tax rates. With Australia’s means-tested social security system many Australians will have experienced extra work hours not being financially worthwhile or, worse, their disposable income going down despite their nominal income going up. It’s not just an issue for the HELP repayment system.

But an EMTR rationale is still going to seem like a rather technical justification that many HELP debtors will not care about very much.

As noted in my first marginal rate post, a high HELP repayment EMTR can mess with cash flow but it still contributes to clearing debt. It is not as bad as other EMTR issues, which lead to permanent income loss.

The EMTR argument will also be complicated because a multi-marginal rate student loan repayment system, especially compared to single rate systems such as those in England and New Zealand, still has this problem – albeit well below the 100% or more rates suffered by some current HELP debtors. This will particularly be the case if, as seems likely with the Accord model, the first marginal rate is set at a low rate. To maintain total repayment revenue, this inevitably requires much higher rates further up the income distribution than would otherwise be necessary.

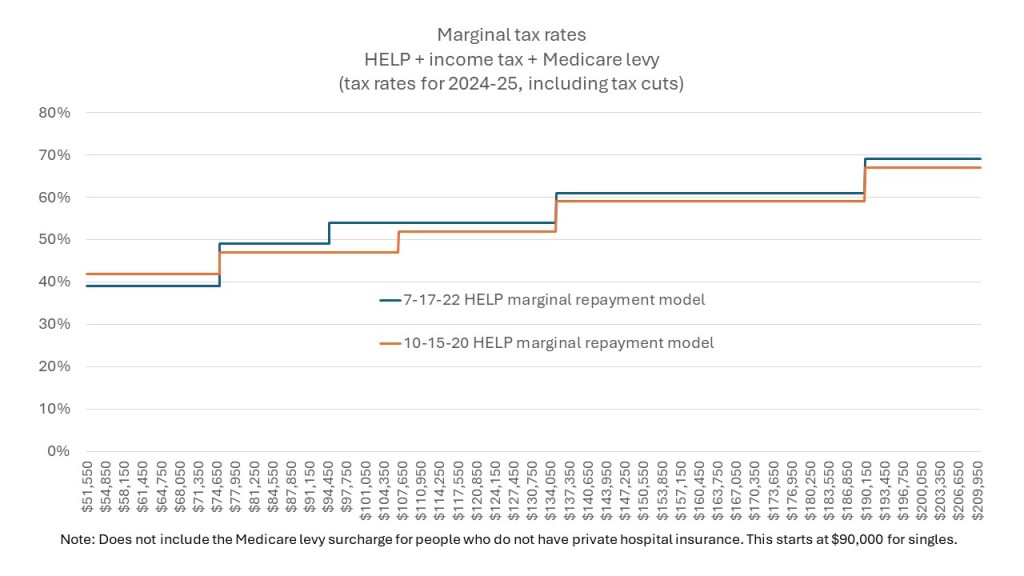

Under both my marginal HELP repayment models in the previous post, people on common early career graduate salaries – including the median 3-year out salary for people with undergraduate qualifications – will have marginal rates – including HELP, income tax and the Medicare levy – close to 50%. Higher income HELP debtors would face EMTRs over 60%, as the chart below shows.

Compared to the current HELP repayment system, with its 18 thresholds and rates causing HELP EMTRs to bounce around in ways that cannot be easily calculated without a spreadsheet, any of the marginal rate options would provide a clear percentage amount. The marginal rate EMTRs may therefore influence behaviour more than the sometimes higher, but much harder to understand, EMTRs of the current system.

Of course the income tax rate is the main driver of the total EMTR, with the tax cuts starting 1 July 2024 improving HELP debtor EMTRs for some people. If we are going to set clearly visible high marginal HELP repayment rates introducing them simultaneously with offsetting tax cuts would be good timing.

Selling a marginal rate system as reducing repayments

As noted earlier, lower annual repayments are not an inherent feature of marginal rate systems compared to a % of all income system.

A flat 13% system would increase repayments for many lower-income HELP debtors and the 10%-15% part of my 10%-15%-20% model would leave many people with roughly the same absolute repayment amounts as now.

It would be a policy decision to lower annual repayments. It could be done under the current system, by increasing repayment thresholds and/or reducing repayment rates, or with a marginal rate system such as my 7-17-22 example.

As with the EMTR argument, the lower repayment point would need caveats. To make the repayment sums add up, at least in the way needed to get expenditure review committee approval, some HELP debtors on higher incomes would need to repay more each year.

Are lower repayments necessarily a longer-term positive for the debtor?

The Accord final report assumes that reduced annual repayments for HELP debtors on lower incomes are a good thing. As someone who thinks that student funding systems are essentially income smoothing devices this is a big issue.

Is it better to clear HELP debts in smaller annual amounts over a larger number of years, so that these repayments have less of an impact on disposable income as people manage their cost of living, look to buy homes and think about starting a family, or is it better to clear debts quickly so that HELP repayments are no longer required at all?

Of course people who prefer to pay off their HELP debt more quickly can top up their compulsory repayments with voluntary repayments.

But systems that require higher annual repayments than most people, with current consumption possibilities in mind, would choose in the short term can be better in the long run. Superannuation and mortgage repayments are examples of forced savings systems that can leave us better off in future decades.

The policy issues aside, high indexation rates have highlighted the disadvantages, both personally and politically, of HELP debtors with high HELP balances over long periods of time. With slower repayments indexation will be applied to larger balances in a greater number of years.

My proposal for capped indexation would help manage the politics of HELP debt. But policy generally should be trying to keep debt and debtor numbers down. The Accord interim report prompted tougher measures on disengaged students, so they do not pointlessly accrue HELP debt for subjects they are not actually studying. The proposed reform of student contributions, to link them with expected earnings, may not change the total amount borrowed. But it will transfer debt to people better placed to repay it in a reasonable timeframe. Lower annual repayments, however, take policy in the other direction, towards longer average repayment times for HELP debtors whose incomes never reach the levels where annual repayments are larger than under the current system.

Cost of living and inflation adjustments

It should also be kept in mind that indexed repayment systems – presuming there is inflation – automatically lower how much is repaid at a given income level.

The minister says that someone on $75K could repay $1,000 a year less on the unspecified system he has in mind. But someone on $75K already had a $750 repayment cut due to indexation of current thresholds between 2022-23 and 2023-24. There was a flukish element to this. The quirks of the current 18 threshold system meant that someone on exactly $75K was pushed back two rates, from 4.5% to 3.5%. Another person on $75,150 had their repayment reduced by $375.

These quirks aside, the current system automatically makes cost of living adjustments, as would an indexed marginal rate system.

Disposable income shocks to higher income HELP debtors

When the lower HELP threshold rates were introduced over 2017-18 and 2018-19 people complained that the rules of the game had unfairly changed. Incomes they expected to be free of HELP repayments suddenly required a repayment.

While I don’t think such complaints should automatically be classed as more important than other policy considerations, generally stable rules around which people can make plans and commitments are desirable.

My 10-15-20 model does require larger annual repayments on higher income earners than the current system but these are smaller than under the 7-17-22 model. With the 7-17-22 model, compared to the current system, a person earning about $132K repays $2,000 a year more, someone on about $157K repays about $3,000 a year more, and someone on about $165K repays $4,000 a year more.

These people are a fairly small proportion of all repaying debtors, about 7% on 2021-22 data. Nevertheless these increases are large enough to get a reaction, especially from people already suffering from higher mortgage repayments.

And while APRA should reverse its silly decision to include total HELP debt when calculating debt-to-income ratios in assessing maximum mortgage amounts, annual repayments directly affect a person’s ability to service a mortgage. People in income bands with significantly higher repayment amounts than now would have lower borrowing caps, as their capacity to repay a home loan has declined.

Conclusion

If we could go back to 1988, when the whole-of-income HECS repayment model was proposed by the Wran report (with no discussion of the alternatives), I’d probably say no, let’s have a single-rate marginal system instead.

Fixing this mistake now, however, would not be politically easy. The 13% (or thereabouts) single rate needed to raise roughly the same amount of repayment revenue as now would mean repayment increases for many low-to-medium income HELP debtors, while high income debtors would repay less per year. This political consideration is likely to outweigh the benefits of slightly shorter repayment times for most debtors and a consistent easing of the EMTR problem.

The multi-rate marginal system implied by Accord final report was presumably intended to avoid higher repayments at the lower end of the HELP debtor range. While a multi-rate system would reduce EMTRs for lower income repaying HELP debtors, elevated EMTRs would still be a feature of the system, and in some cases would exceed EMTRs in the current repayment model. EMTRs on a marginal rate system would be easier to understand than now, which may increase the number of people whose behaviour is influenced by them.

Although a reduced annual repayment on lower incomes is not an inherent feature of marginal rate systems, it is likely to be a feature of the version flowing from the Accord final report. I am not persuaded that longer repayment times are self-evidently good for HELP debtors over the long run. They would not be good for HELP’s overall finances either. With the Accord final report recommending massive new higher education spending, additional subsidies for HELP should not be a priority.

Add to these policy concerns the political difficulties involved in explaining EMTRs in the first place and why a 7% repayment rate is really less than a 1% repayment rate.

This could all get very messy and not worth the effort.

Many thanks, great explanation as to options for rejig of HELP repayments.

Is it your expectation a policy of ‘universal application’ will apply ie regardless of students having had the benefit of CSP support or not?

LikeLike

Yes. All ICLs whether higher ed (with now 5 HELP sub-schemes), voc ed (2 sub-schemes and one legacy scheme) or DSS (1 scheme and one legacy scheme) currently have the same repayment thresholds and rates. It would be administratively chaotic to do it any other way. Employers have to be able to work out the correct PAYG deductions, debtors who may have several types of ICL debt need clarity on their repayment obligations.

LikeLike