In two previous posts on higher education parallels between Britain and Australia, prompted by reading Peter Mandler’s book on Britain, I also noted that there were some important differences, which this post explores.

National versus regional systems

Mandler argues that in Britain a national higher education system emerged out of a ‘patchwork of institutions dating back to the middle ages’. Although local funding has been part of higher education finance in Britain, national funding was more significant early in the 20th century, and dominated the post-WW2 expansion of higher education. Universities were linked in a common funding system.

As a recent book by Gwil Croucher and James Waghorne explains, in Australia state governments were significant funders of higher education until the national government took over in 1974. Laws regulating the foundation of universities were state-based until 2011, although agreements between the states created a high degree of uniformity from 2000.

In Britain, free higher education from 1962 and a means-tested maintenance (income support) grant helped universities recruit nationally. Britain had a national applications and admissions system from 1961. However, devolution in the UK means that there are now differences in higher education finance between jurisdictions.

Free or consistently-priced undergraduate education across Australia since 1974, along with means-tested student income support, has not fundamentally changed the largely regional nature of Australian higher education. Most students attend universities in their state, and usually in their home city. Australia’s admission systems remain state-based.

Of course, a national market is much easier in a geographically small country like Britain than a geographically large country like Australia.

Living away from home

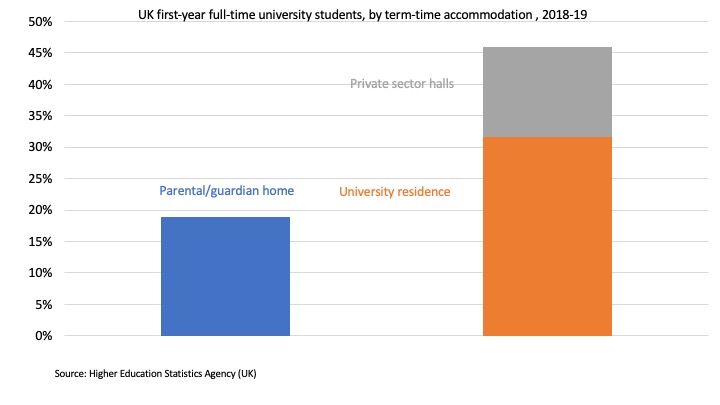

A high willingness of students to live away from home underpins a British national higher education market. The chart below shows that less than 20 per cent of UK full-time first-year students live with their parents. The population of first-year students include some older people who would have moved out before commencing their university studies, but more than 45 per cent of students live in university or private sector student residences.

In Australia student practices are very different. Only about 10 per cent live in university accommodation, and at age 18 nearly 80 per cent have a census household status as ‘dependent student’; mostly they live with their parents.

These patterns of attending university mean that higher education plays a different socialisation role in Britain compared to Australia. Although Britain’s relatively small size means that home is never that far away, students leave their local communities and join a university community. In Australia, commuter campuses mean that most students maintain a daily connection with their families and where they grew up. It would be fascinating to see a comparative study on how this affects long-term friendships, careers, and places of residence.

Universities and a national market

In Australia, students can choose to move to study, and so in theory universities compete with institutions across the country. But the unwillingness of Australian compared to British students to move protects universities – a non-local university might be a better match for a student, but that university is at a big competitive disadvantage if it is outside the student’s commuting distance.

In Britain, moving out to study is mostly done for cultural reasons, part of a rite of passage. It is not primarily a market exercise in finding the optimal educational choice. But once a move is assumed British students can take into account university-specific factors that most Australian students ignore if the university is too far away.

Mobile students made demand driven university funding more destabilising in England than it was in Australia. The main justification for recapping funding in England was to protect vulnerable universities from losing too many students. The more regional nature of Australian higher education markets helped minimise that risk here. Although some Australian universities did not expand much under demand driven funding, none shrank. In Australia too much demand and its associated public spending cost, not university fear of competition, triggered spending caps.

Elite national institutions

No Australian university dominates education of the future national elites in the way of Oxford and Cambridge in Britain (although Australia is not immune from Oxford’s influence; only the University of Sydney has educated more prime ministers).

Although Australia’s national elites are disproportionately educated at Group of Eight universities, no Gof8 university has achieved a dominant national position in undergraduate education.

All Gof8 universities are government founded, and seven were established to meet local needs that remain core functions. The reluctance of Australian students to move, and the general lack of a compelling reason to do so, means that most domestic students at Gof8 universities are local or from a within-state regional area. None can attract and congregate the smartest school leavers from across the country.

All Gof8s operate at a scale that works against Oxbridge-level exclusiveness. In a country with more than twice Australia’s population, Oxford and Cambridge have much smaller annual domestic undergraduate intakes, about 2,600 students each, than any Group of Eight university, which in 2019 ranged from 3,152 (ANU) to 8,162 (UQ).

That the Gof8 universities are not that elite, compared to the leading UK universities, gives Australian higher education an overall more egalitarian character. Analysis I worked on at the Grattan Institute, and that of others, found no large income premium from holding a Gof8 degree, while an Institute of Fiscal Studies analysis found that graduates from ‘top’ universities like Oxford and the LSE earn significantly higher incomes than graduates of other universities.

Conclusion

Both the British and Australian higher education systems are open to the vast majority of students who want to attend. But they differ significantly in the social experience of higher education, and in the sharpness of status distinctions, which in Britain leave some universities quite vulnerable while others, and their students, are part of a national and global elite.

The high proportion of students living away from home in the UK makes higher education much more expensive than in Australia, making the size of student debt much more of an issue.

There is evidence that student engagement and satisfaction is higher for students living in university residence.

LikeLiked by 1 person