In 2018, applications from school leavers for university entry were much the same as in 2017. But from non-Year 12 applicants, demand dropped by more than 5 per cent. Full 2018 enrolment data is not yet available, but first-semester domestic commencing undergraduate enrolments fell by 1.8 per cent. Various media reports suggest that demand in 2019 will be lower than in 2018.

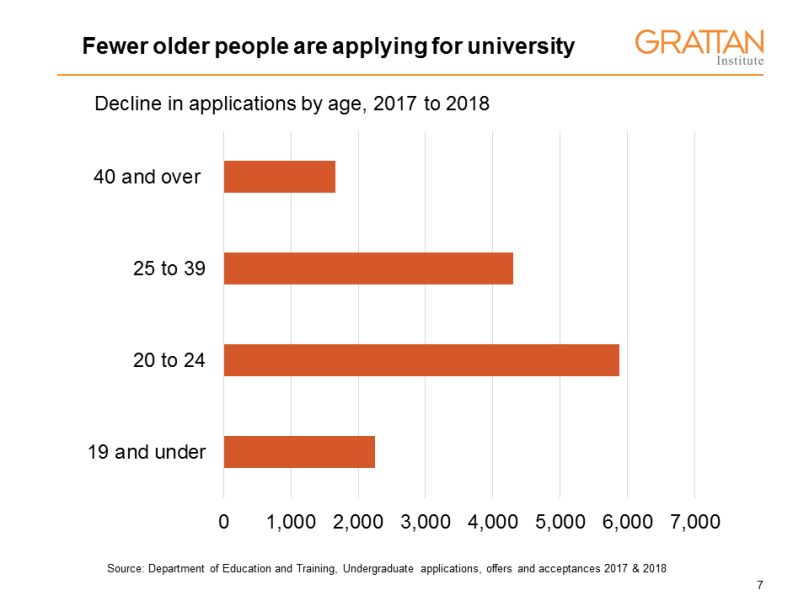

As the chart below shows, the largest absolute drop in applications is for people aged 20 to 24, but in percentage terms the older groups dropped at around the same rate.

Looking at the data on prior education for the non-Year 12 group, application numbers are holding for people with sub-bachelor and vocational qualifications. But the no prior tertiary education and repeat-customer higher education groups are both in decline.

People changing courses or taking another course have long been a significant component of each year’s commencing students, but during the demand driven era they increased from 23.5 per cent in 2008 to 29 per cent in 2016.

Because repeat customers are such a large part of each year’s commencing students, this hid the fact that the number of new-to-higher education students started decreasing in 2015, three years before the total number of commencing students went down. As with the more recent data, the decline was concentrated in the older age groups, as the chart below shows. One theory is that as more people go to university straight after school more of the underlying demand for higher education is satisfied at this point, and so there will be fewer mature age students. The growth in 17-19 year old enrolments shown in the chart above interacted with fairly stable demographics to produce a big increase in participation rates, as seen in the chart below.

One theory is that as more people go to university straight after school more of the underlying demand for higher education is satisfied at this point, and so there will be fewer mature age students. The growth in 17-19 year old enrolments shown in the chart above interacted with fairly stable demographics to produce a big increase in participation rates, as seen in the chart below. But this leaves an open question as to whether there are substantial numbers of people in older age groups who did not go to university in earlier years but would still like to. ‘Unmet demand’ used to be a major issue in higher education policy, with participation rates constrained by government and university supply decisions.

But this leaves an open question as to whether there are substantial numbers of people in older age groups who did not go to university in earlier years but would still like to. ‘Unmet demand’ used to be a major issue in higher education policy, with participation rates constrained by government and university supply decisions.

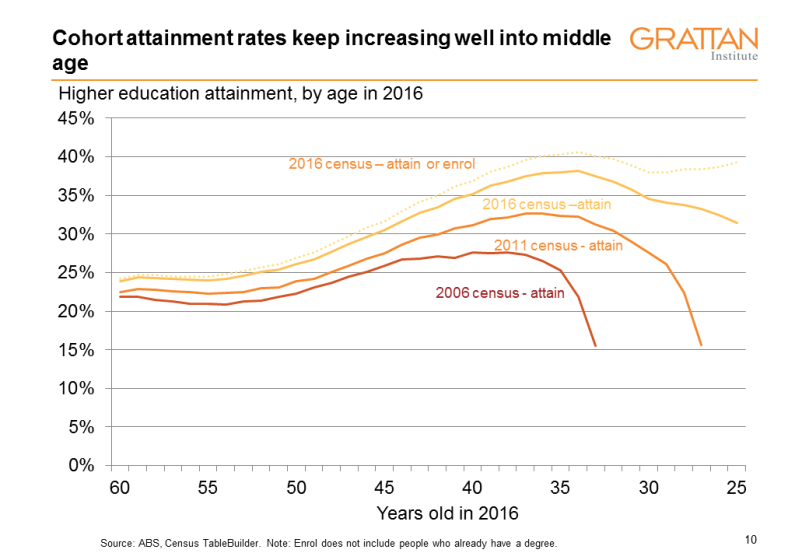

Consistent with this underlying demand, the Census suggests that cohort attainment rates keep growing long after the main post-school university-attending years (chart below). But if we assume that attainment will reach some stable point around 40 per cent, then we are at or close to that (counting current enrolments as well) for the cohorts aged 40 or less. History suggests that some older people will continue to seek further education, but that it will be a small additional proportion of their age cohort, and have a modest effect on total enrolments.  While recent weakness in mature-age enrolments could be due to structural factors, higher education has a counter-cyclical element as well – when jobs are scarce we would expect more people to go to university, while when jobs are easier to find we would expect fewer people to go to university.

While recent weakness in mature-age enrolments could be due to structural factors, higher education has a counter-cyclical element as well – when jobs are scarce we would expect more people to go to university, while when jobs are easier to find we would expect fewer people to go to university.

As the chart below shows, the number of employed persons in key mature-age student demographics has been increasing. The employment to population ratio for 25-34 year olds has been at or near record levels since late 2017 (over 80 per cent in all but two months), although only modestly up on the more typical 78-79 per cent of recent years. Still, this could help explain why slightly fewer older people feel the need to study to advance their job prospects or careers.

We can see from earlier years in the chart that the number of jobs fluctuates over time, and this current growth period will come to an end. When it does, we might expect demand for higher education from prospective mature age students to increase again.  The structural and cyclical explanations of recent applications trends are not mutually exclusive. But my best guess is that we will not see another major surge of demand for undergraduate courses from mature-age applicants. For people currently aged in their mid-30s or less, most of the people who might have seriously considered going to university have already done so. Although there will be cyclical ups-and-downs, the long-term trend is likely to be towards fewer people commencing their studies aged 25 or older.

The structural and cyclical explanations of recent applications trends are not mutually exclusive. But my best guess is that we will not see another major surge of demand for undergraduate courses from mature-age applicants. For people currently aged in their mid-30s or less, most of the people who might have seriously considered going to university have already done so. Although there will be cyclical ups-and-downs, the long-term trend is likely to be towards fewer people commencing their studies aged 25 or older.

Great insight as always Andrew

In my opinion – I suspect that the unmet demand has largely been satisfied in older cohorts – and when combined with increasing school leaver participation rates may have a bearing on mature age undergraduate demand. This assumes sustained lower rates of participation for regional and other communities.

However with the need to retrain and upskill rising – the large pool of those with undergraduate qualifications and new to stay one step ahead of the Joneses will see sustained growth in postgraduate education.

Universities won’t need to be planning to downsize anytime soon ….-unless the international market collapses.

LikeLike

[…] affect students too much. Demand has been soft since 2015 and fell in 2018, mainly because fewer older people wanted to study. Early indications are that demand fell again in […]

LikeLike