When the Accord final report was published one recommendation that confused me was a policy to increase equity student enrolments that was “effectively ‘demand driven for equity’ but with planned allocation of places to universities”.

A demand driven system, under which universities can enrol unlimited numbers of students meeting set criteria, can sit alongside a system of allocated student places or funding. Current Indigenous bachelor degree demand driven funding, which would be retained in the Accord model, sits alongside a soft capped block grant for most other students. But for the same courses, or student categories, demand driven and allocated student place systems are mutually exclusive.

Any hope of clarity has been dashed by the Accord implementation paper on managed growth. It proposes “managed demand driven funding for equity students”.

Capacity to meet demand compared to demand driven

Questions to officials when the Accord report was released indicated that the idea was to provide sufficient places to meet equity applicant demand.

A capped system can de facto operate similarly to a demand driven system, if demand is sufficiently below the caps that universities can respond positively to most applicants.

But the government now proposes a hard capped system, with no student contribution only places. The caps for fully-funded places in 2026 are forecast to be so low that the government proposes transition arrangements for universities that need to reduce their full-time equivalent CSP enrolments.

The problems “managed demand driven funding” seeks to fix are partly a consequence of the government’s own misguided policy of hard capping CSP EFTSL.

Managed equity admissions

What the government proposes instead of demand driven funding for equity students is a system perhaps best described as “managed equity admissions”.

This is a system that attempts, within its constraints, to enrol as many equity students as possible.

The equity groups covered

The equity groups covered are low SES, regional or remote, and students with disability. The consultation paper list of “implementation issues for consideration” recognises the definitional issues involved. I hope to write about these in more detail elsewhere, as the ethical and administrative issues are significant.

Neither the low SES nor regional or remote categories are designed to award individual benefits such as a university places. They are both based on geographic proxies, not individual characteristics. They include false positives, people with few or no personal indicators of disadvantage. The children of highly educated and wealthy parents living in regional areas would be eligible for managed equity admission CSPs.

More significantly, these geographic proxies produce false negatives – people living in metropolitan areas that are not classified as the lowest 25% by the ABS Index of Education and Occupation, but who would personally meet normal indicators of disadvantage, such as low family income and low family highest educational attainment.

The administrative benefit of geographic proxies, however, is that they can be determined from address information that applicants already provide. Applicants do not need to self-identify as disadvantaged or submit any additional paperwork.

Disability is administratively more complex. I’m not sure that it is routinely collected in the applications process – it is not in the national applications data. Disability would need to be incorporated into applications for managed equity admissions to work. Under the Accord system, both applicants (for admissions preference) and universities (for the promised needs based funding) have an incentive to claim disability status. Taking lessons from the NDIS, a system of verifying disability status would be required. All of this would significantly increase the time and cost involved in making and assessing applications.

The size of the equity cohort

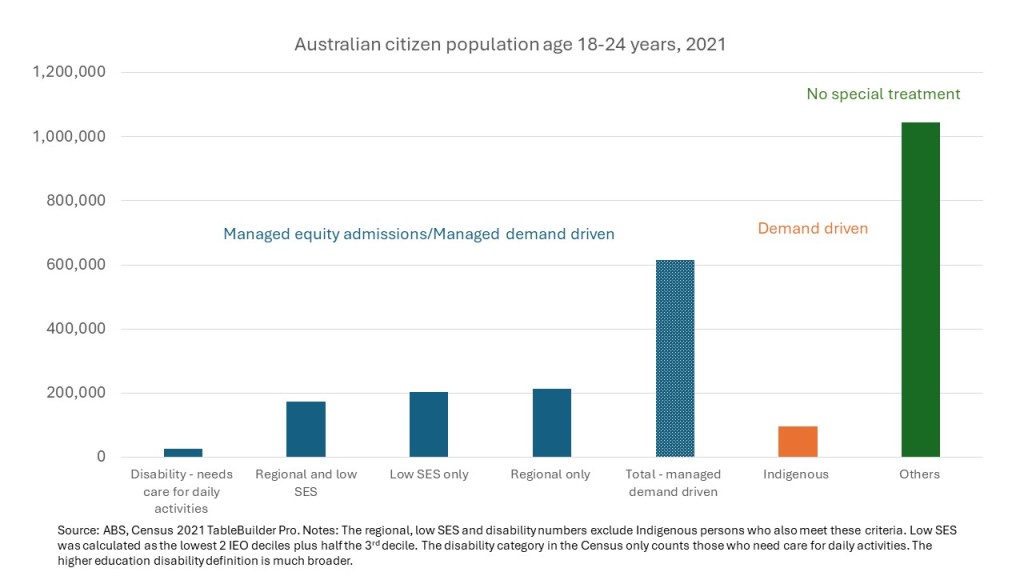

The disability question in the Census only counts people who need assistance with daily activities, a much smaller group than qualify as having a disability in the higher education data. Even with this restriction on a full count of the included population, more than 600,000 Australians age 18-24 years in 2021, or 35% of all the cohort, would be eligible for assistance under the managed equity admissions/managed demand driven system.

The trigger for new assistance

The Accord final report suggested that “the funding system should support all Australians who wish to study and who meet entry requirements to higher education” (emphasis added).

As I said on the final report’s release models for such a policy exist in Australia’s past and in Europe today. People who meet threshold academic requirements are entitled to a place. But who decides on the entry requirements?

An otherwise confusing sentence in the consultation paper may have the answer, emphasis added:

“Students from equity backgrounds wishing to study [at a Table A university, except medicine] will be guaranteed a fully-funded CSP if they gain admission, but not guaranteed a place at their chosen university.”

Anyone who actually “gains admission” is already guaranteed a place, conditional on filling in some forms. That’s how the current system works – backed up by section 36-30 of the Higher Education Support Act 2003 for CSP domestic undergraduates.

Perhaps what this means is that Table A universities do the entitlement screening, creating a category of applicants who are suitable for admission but who are not in fact admitted due to the hard cap the government would impose on CSP EFTSL. This is supported by the minister’s statement today that the government was “uncapping [sic] the number of places at university for students from disadvantaged backgrounds who get the marks for the course they want to do”.

For the process discussed below to work, this information on the reason for no offer would need to be flagged in some central admissions system. (The number of such entries should be included in metrics on ATEC’s performance – the higher the number, the worse its performance in allocating CSPs.)

The applicant’s preference list

We already have a system for maximising an applicant’s chance of getting a place. If using a tertiary admission centre, prospective students can apply for multiple courses at once. If the applicant does not receive an offer for their first preference course they are considered for their second preference, and so on until an offer is received or the preference list is exhausted.

The consultation paper says that this process will similarly apply in the managed equity admissions system. Its processes would apply after the preference list is exhausted.

Direct applications create a complexity. While TACs sometimes run these behind the scenes, it could be the case that nobody other than the applicant has full visibility on all their applications. This also suggests that this policy would need a centralised admissions system that could keep track of the status of each applicant.

But eventually some applicants will exhaust all their options without an offer.

Supplementary offers

The next stop in the process, as described by the consultation paper, is something like the Victorian supplementary offer system. This means that applicants can be offered a course that was not on their preference list but is in the right “student catchment area”.

Perhaps AI could be used to identify courses that are similar to, or draw on similar interests to, the courses the applicant had on their original preference list.

Perhaps estimates of travel times between the applicant’s home address and the location of alternative courses could be used to determine the relevant “catchment area”.

If the student had applied for an online course, the catchment area could potentially be anywhere in the country.

I don’t think this step of the process needs to know whether previous rejections were due to capacity constraints or other factors.

But it does rely on the supplementary offer universities having spare capacity within their managed growth target (MGT) EFTSL.

All local universities at their cap

If no university in the applicant’s catchment area has made an offer for capacity reasons there is scope to return to ATEC for additional CSPs. The consultation paper says these CSPs could be redirected from elsewhere in the system or be additional places.

It’s not clear how ATEC will determine whether there is excess capacity elsewhere in the system, unless a university is invoking the funding floor protection discussed in an earlier post.

If the TCSI system is operating effectively (a big if) ATEC simulations could estimate CSP EFTSL used, based on enrolments to date, across the country. But universities might want to keep EFTSL free for a mid-year intake. Universities may also decide to keep commencements down as a guard against lower attrition rates or higher full-time study rates than estimated, which could push their CSP EFTSL over the hard cap.

Redirected places could be lost for a multi-year period so that the student at another university can complete their course. So that would require multi-year modelling of the impact of a redirect on the university losing places.

Critically, this process will cost time. The applicant will already have moved through the standard offer rounds and the supplementary offer process, getting closer and closer to course commencement dates. Analysis of potential sources of additional places and a process for redirecting them would take more time. If this fails, ATEC would have a further internal process to determine whether it can provide additional places.

Such a convoluted process on a tight timeline raises basic practicality concerns.

Which university gets the extra places?

The additional places system would also need a mechanism for deciding which university on the applicant’s preference list gets the additional places.

Presumably the applicant’s first preference university would have the strongest claim. But would they want the applicant without a multi-year EFTSL commitment? Do they want to take additional EFTSL on very short notice?

Can they reject the applicant a second time?

And what happens if the number of additional places is below the number of students that missed out? A new selection process would be needed.

And what incentives do these complications create? Perhaps one incentive is to not flag an applicant as having missed out due to capacity issues in the first place, because this could create administrative hassles later on.

The position of the applicant

What happens to the applicant during this process?

Are they told about what is happening behind the scenes? If so, who is responsible for this communication?

Are they asked whether they want a supplementary offer? Their original preference list may reflect careful consideration of potential courses, with these the only courses they would take.

Are they asked whether they want a process of negotiating funding if they receive no offers?

Would they rather have a quick result either way, so if negative they can move on to their TAFE or work Plan B?

Conclusion

The name “managed demand driven funding” is confusing and contradictory. A new name would make the confusion and contradiction less self-evident, but not remove it from the policy framework. A policy for maximising enrolments and a hard cap policy are contradictions. The process for trying to use all of the theoretical national CSP cap, through moving CSPs around the system in the weeks before course commencement, would be complex and confusing for students, universities, and ATEC itself.

The beauty of an actual demand driven system, as opposed to a managed system however described, is that these issues disappear. If a university has the internal capacity to take an equity student the offer is made, with no worrying about funding caps or ATEC processes. Unsurprisingly, low SES enrolments surged during the actual demand driven system.

The managed demand driven funding proposal is an unsalvageable bureaucratic mess. It should be abandoned.

Instead, ATEC should be made responsible for its initial distribution of student places. There is low hanging fruit here. So far as I know, nobody has ever used Year 12 results or no-offer applications data to see where potential equity group students live. Do it and put some extra capacity in those areas. And let all universities accept students above their cap, so if equity applicants appear in unexpected places there are no bureaucratic obstacles to quick offers.

Thanks Andrew! I’ve a long comment…

Can you elaborate on why you believe the “The caps for fully-funded places in 2026 are forecast to be so low that the government proposes transition arrangements for universities that need to reduce their full-time equivalent CSP enrolments.”?

My understanding is that the “System-wide Pool” is based on the projected needs for CSPs to meet the Accord’s 2035 interim targets, and that the Pool is the sum of all university Managed Growth Targets (MGTs). The Accord Final Report estimates that this would require “…a more than doubling of the number of Commonwealth supported students from current, 2022 levels (860,000) through to 2035 (at least 1.2 million) and 2050 (at least 1.8 million).” (p. 1). This equates to 40% more CSPs in 2035 compared to 2022, or ~2.5% annual growth. But the university sector is likely already behind its interim targets due to soft demand in 2023 and 2024 (e.g. NSW TAC data suggests 2024 is down ~5% compared with 2022). Therefore, I would think that the Pool would need to be much larger than current CSP demand if it is to support the 2035 sectoral target. If the Pool is sufficiently large – even set at 2022 levels – then few universities will be pushing up against the MGT, and the MGT as a mechanism to re-direct demand, will be largely irrelevant.

My understanding of the transition funding is that it is partly to support the transition from MBGA to MGT (e.g. over-enrolled universities), but mostly to protect those universities whose demand drops annually under the MGT system without the continuity guarantee by providing some guaranteed % of the MGT from the previous year irrespective of enrolments.

Overall, the MGT is trying to do many things at once (e.g. redirect CSPs between universities; guarantee places for equity students; project demand for higher education; provide institutional stability/base funding; increase responsiveness to skills, government and industry needs; “simplify” the current system). I think the way to minimise the unintended consequences would be to initially have a very large Pool so that most students go to where they want to and are funded, and a relatively lower “floor funding” as a % of MGT (which ought to be larger under a very large pool). If the sector looks to be on track for the 2035 targets, then start using the MGT as a mechanism to redirect within the system.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Peter – The first point is a reference to unis expected to be over-enrolled in 2025 being allowed to keep student contributions for pre-2026 students if above their MGT EFTSL during 2026-2029, discussed in this earlier post. There would be no need for this transition arrangement unless the 2026 MGT EFTSL is going to be below actual 2025 EFTSL.

It suggests that they plan the system start to be something like what EFTSL would have been if a uni had reached its MGBA.

It’s true that the Accord recommended growth in CSPs. But I am sceptical. The minister has had few major wins in Cabinet to date for higher education. Even minor spends like the DDS for all Indigenous bachelor students had offsets. The largest apparent win was on HELP indexation, but even then he probably won only because the medium term cash flow cost was not massive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is from Peter but the system was blocking it:

Thanks, I see your point, but if we can trust the words of the discussion papers, the Pool will need to be larger than current demand. Assuming the government’s target is what is in the Accord Final Report (a reasonable assumption, I think) then the Pool needs to be sufficient to meet that target.

To quote the MGT paper:

“The Government will determine a maximum system-wide pool of Commonwealth supported places to support the long-term growth in enrolments to reach the Government’s attainment targets. Eligible institutions will negotiate a Managed Growth Target (MGT, expressed in numbers of students enrolled) from the system-wide pool of student places.”

The Government determine the Pool based on its attainment target and with advice from ATEC. ATEC then negotiate with universities to determine individual MGTs.

To quote the ATEC paper, ATEC will:

“Provide for a diverse sector that better meets student demand through allocating Managed Growth Targets for places to individual institutions, within the system-wide pool of Commonwealth supported places (CSPs) determined by Government.”

Therefore, ATEC will be able to determine a university’s 2026 MGT EFTSL, not Government. ATEC could determine it to be at, above or below actual 2025 MBGA EFTSL. If it is below the 2025 MBGA, then a university gets to keep student contributions until 2029. If the Pool is sufficiently large, then there would be scope to set 2026 MGTs above the 2025 MBGA EFTSL for the over-enrolled universities. The others that are under-enrolled would have MGTs at or below their 2025 MBGA EFTSL (which would entail growth, because they are under-enrolled). The sum of university MGTs could easily be within the Pool, even allowing for all universities to grow.

Overall, if the 2026 Pool (i.e. sum of MGTs) does not grow compared with 2025 EFTSL and in line with the 2035 target (which I think would need ~660,000 CSP EFTSL in 2026 vs 610,000 in 2022 and ~575,000 in 2024), it will be literally impossible to meet the Government target. ATEC (and the sector) will be set up to fail. ATEC will be given a Pool that, even if fully enrolled, would not meet the transitional attainment target. The only positive would be that, under constrained growth for non-equity students, it will be easier to achieve population parity because the non-equity cohorts will be denied access.

LikeLike