An earlier post looked at the government’s plans for the Australian Tertiary Education Commission. This post examines the government’s proposals for setting the number of student places and distributing them between universities. This includes a hard institution-level cap on student places, so that universities would get zero funding for enrolments above their allocated level. This post explains why a hard cap is unnecessary and counter-productive.

Overall number of CSPs

The government will determine the total number of CSPs. For ‘fully funded’ places – places for which universities are paid both a Commonwealth and student contribution – this is similar to the current system of the government deciding on total CGS funding, other than the small demand driven system for Indigenous bachelor-degree students (which will be retained). However,

- because universities will have flexibility in moving EFTSL between disciplines (discussed in a later post) the maximum dollar amount the government pays will be less predictable than now.

- because of the first point and hard caps on student places at each university (discussed below) the maximum number of CSPs the system provides will be more predictable than now.

It is not clear whether ATEC will advise the government on the number of CSPs, as opposed to contextual factors such as demographics, demand, and skills needs.

And if ATEC does provide advice on system-level numbers, it is not clear whether this will be published or not. The consultation paper mentions the state of the sector report recommended by the Universities Accord final report, but this is framed as a ‘report on higher education outcomes’, not future higher education needs.

Former higher education commissions provided detailed public advice on likely student demand and the sector’s capacity to meet it. For an education minister there is a trade-off. Public and quality advice gives leverage in Cabinet when arguing for money and a semi-independent justification for the government’s overall policy direction. But if the minister does not get the money the sector, and opposition MPs, will use ATEC reports against the government.

Distribution of CSPs

ATEC will distribute CSPs between universities. Each university would get a ‘managed growth target’ (MGT), expressed in EFTSL, which would also function as a cap. Institution-level MGTs would be designed to achieve national objectives in the aggregate, but micro-factors at the institution level would include ‘student demand, institutional goals and missions, and institutional and sector sustainability’.

The EFTSL allocation would replace the current Maximum Basic Grant Amount (MBGA), a dollar figure that can convert into a range of different EFTSL amounts.

Bringing new providers into the system is also foreshadowed.

International students

ATEC will provide ‘estimates of student load across funding clusters for both domestic and international students’ (emphasis added). What do funding clusters setting Commonwealth subsidies for CSPs have to do with international students?

Despite this strange choice of metric, it will be part of ATEC’s responsibility to ‘manage international student profiles for public universities’. Some in the sector have called for ATEC’s involvement as an alternative to, and a delaying tactic for, the disastrous ESOS amendments.

ATEC control is unlikely to be worse than the planned personal ministerial control. But it is a concerning sign that the government seriously plans to make controlling international student enrolments a long-term part of the system, and not just a pre-2025 election measure to persuade voters it is getting net overseas migration under control.

The Accord EFTSL tolerance band has changed significantly

The institution-level funding arrangements differ from those recommended by the Accord final report. The original proposal was for student place allocations to be expressed in a ‘tolerance band’ rather than a single, fixed number. The upper level was to be a ‘stretch target’ to drive sector-level growth, while the lower level was a funding floor, to limit the financial consequences of falling enrolments.

The Accord expectation seemed to be that EFTSL would typically land somewhere in the middle, but universities would be funded up to the top of the tolerance band. That top point, however, would be a hard cap – no Commonwealth contribution, no student contribution. We currently have a soft cap – no Commonwealth contribution if the value of places delivered exceeded the university’s maximum basic grant amount, but universities can keep all student contributions.

In the consultation papers there is still a funding floor – although in a different form to the Accord recommendation, discussed in a subsequent post – but the language of tolerance bands and stretch targets is gone. There is just the managed growth target (same MGT abbreviation, but it was variously this and a ‘moderated growth target’ in the Accord) which, as in the Accord, is also a hard cap.

A target and a cap?

Perhaps the issue is just choice of words, as a funding range will still exist, but the same EFTSL number cannot easily be both a growth target and a hard cap. A growth target implies an aspirational number to which a university should aim, a hard cap implies a boundary that it should not breach.

As with the proposed international student caps, the consultation papers display obliviousness about student load management and how difficult it is to hit a precise EFSTL number. Important variables that determine the EFTSL outcome – offer acceptance rates, mix of part & full-time enrolments, and attrition – can be estimated and influenced but not controlled.

The current soft cap system provides an over-enrolment insurance policy for universities that overshoot their funding agreement maximum basic grant amount. They won’t get the Commonwealth contribution but they will get the student contribution. Student contribution only places perform a similar function to the proposed funding floor – they reduce the financial effects of enrolment fluctuations above and below the allocated level.

As a hard cap increases the risk of exceeding the MGT – because the university will have students who cost money but bring in no revenue – the logic of the system is for universities to set internal targets below the MGT. The gap between the internal and ATEC targets would serve as the university’s safety margin, if EFTSL achieved exceeds EFTSL estimated.

Universities aiming for EFTSL below the MGT would be a negative for the government. At a system level, overall ATEC targets would be less likely to be reached. Financially, the government would pay full price for every student place in the system, when based on history it could get a few per cent of places for just the costs of running HELP.

Why are over-enrolments bad? – the system stability argument

In the current consultation paper the reason given for a hard cap is that over-enrolments ‘create adverse flow-on impacts for the whole system’. No evidence or argument is provided in support of this point.

Over-enrolment and under-enrolment indicate that a bureaucratic allocation of funding or places is misaligned with the preferences of students and (if not a major student load planning error) the teaching capacity of universities.

Redistributing resources to where they are best used should be seen as a system goal rather than an ‘adverse flow-on impact’.

Indeed, the consultation paper accepts this goal in principle if not, it seems, in practice. It rightly criticises the Job-ready Graduates misallocation of growth funding by campus location and says that ‘the new system will more responsively allocate growth to align with student demand’. Over-enrolment is useful information for ATEC rather than a problem.

The consultation paper says that the hard cap will also apply to the six non-Table A providers with CSPs. This offers consistency but not credibility. Expansionary strategies or student load management issues in half a dozen small institutions, spread over four states, could not plausibly inflict adverse impacts on the whole system.

Why are over-enrolments bad? – the quality argument

The government last took a dislike to over-enrolments in the 2000s. From early in his 2001-06 term as education minister Brendan Nelson said over-enrolments were undermining quality, that universities were taking more students than they could properly support.

The first of Nelson’s Crossroads papers in 2002 noted that over-enrolments exceeded 30,000 EFTSL and suggested discontinuing or capping them. The policy as announced proposed a 2% tolerance band above allocated EFTSL, although with additional fully-funded places from 2005. In the final legislation the cap was increased to 5% – so a medium pressure, rather than a soft or hard cap.

Extreme over-enrolment levels are a plausible quality risk. But some part-funded student places do not inherently cause problems. Small numbers of additional students, put in existing courses and using existing infrastructure, do not necessarily cost more than the student contribution revenue they bring in.

If over-enrolment happens by accident, taking away student contribution revenue would exacerbate any quality issues, by depriving the university of revenue to cover additional teaching expenditure.

How would the hard caps be implemented?

The consultation paper does not say exactly how the hard caps would be implemented.

While universities can make decisions that they know will result in over-enrolments it is not practical to identify individual students as ‘over-enrolments’. The full extent of any over-enrolment will not be known until after the final census date of the year, when CSPs delivered can be compared to CSPs allocated.

In the Nelson era the method for determining a penalty was to

- Calculate the average student contribution charged for the full year, and then

- Multiply the average student contribution by the number of places over the cap.

The penalty, however, was a reduction in the university’s Commonwealth Grant Scheme allocation rather than student contribution revenue. Since that time the penalty regime has moved towards fines rather than grant reductions, such as the $18,780 per student fine for breaching the support for students policy. However the language of ‘not permitted to retain student contribution amounts’ suggests that the penalty will not exceed the student contribution amount.

From a student perspective they must all still pay their student contributions. Students could rightly feel aggrieved that money they paid for their teaching is not received in full by their university.

Who suffers the consequences of hard caps?

The university will pay the financial penalty for over-enrolments, by some yet-to-be determined mechanism.

But the pain would be spread more widely.

Students in over-enrolled universities will be disadvantaged by their institution losing teaching revenue.

Teaching staff will be stretched due to more students but no additional money to pay for extra tutors or support staff.

But the people most disadvantaged by hard caps are prospective students. If a university exceeds its cap and needs to reduce EFTSL the easiest variable to control is how many offers it makes to would-be new students.

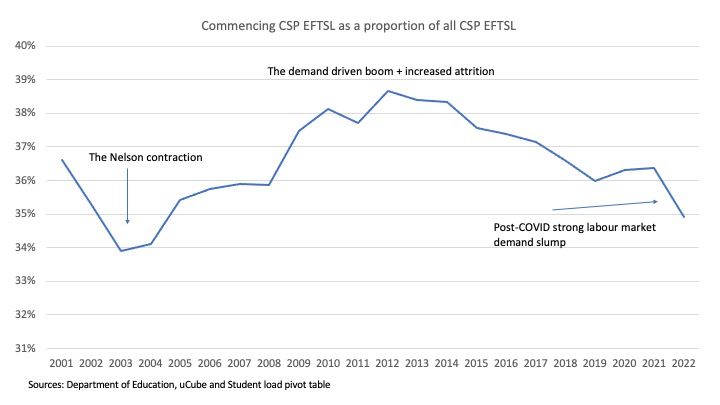

This is what universities did back in the Nelson era. Reading the policy direction, universities reduced their commencing intakes to bring total CSP EFTSL down to allocated levels. As the chart below shows, commencing CSP EFTSL as a share of all CSP EFTSL fell to its lowest point this century.

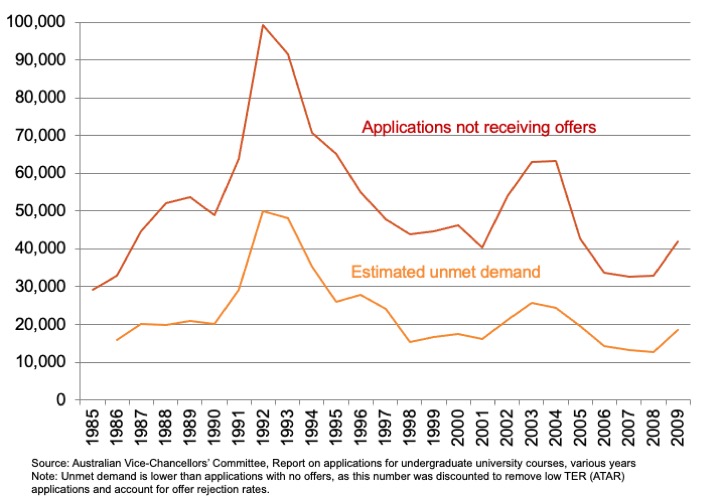

Unsurprisingly unmet demand (as calculated by the AVCC, UA’s predecessor) went up, as seen in the chart below. The commencing student cutback can also be seen in a drop in the age 19 participation rate.

Transition arrangements

The consultation paper suggests a transition arrangement for over-enrolled universities that I do not fully understand.

The policy applies when a university’s CSPs delivered exceed its Managed Growth Targets in the 2026-2029 period. However, a reference to ‘providers that have over-enrolled on their MBGA’ (i.e. enrolled EFTSL with a Commonwealth contribution value exceeding their MBGA under the current funding system) leaves me unclear whether this scheme only applies to universities over-enrolled in 2025, or to any university that over-enrols in the 2026-2029 period. The rationale of avoiding a ‘sudden decline in revenue’ suggests the former.

In 2026, about two-thirds of the students of an over-enrolled university will have started before 2026. They ’caused’ a 2026 or later over-enrolment in the sense that large cohorts of continuing students leave less capacity, in a hard capped system, for future commencing intakes. But since universities cannot arbitrarily cancel the enrolments of continuing students it is prospective commencing students who must miss out.

Perhaps the 2020s transition will work something like the Nelson era over-enrolment system but in reverse. Rather than being fined the average student contribution universities will receive the average student contribution of pre-2026 students, provided the university has pre-2026 students matching or exceeding the over-enrolment margin. That will certainly be the situation in 2026, but may not be in 2029. In that case, the university could receive an average student contribution value for any remaining pre-2026 students, but not 2026 and after students.

The apparent need for this transition arrangement suggests that 2026, and possibly later, MGTs will be below 2025 EFTSL. So this is a MDT, a Managed Decline Target, rather than a MGT. The goal of national enrolment growth does not seem consistent with an institution-level MDT.

On page one of the managed growth consultation paper we are told that the Accord final report found that the current funding system is ‘overly complex, fragmented and difficult to comprehend and needs to be simplified.’

So why introduce a new policy that is overly complex, fragmented and difficult to comprehend?

Conclusion

The hard cap is worse than a solution in search of a problem. It is a solution that will create problems we do not have now. The solution to these future problems is simple: no hard cap.

I don’t believe a cap on student contributions is needed at all. But if the government wants to keep this idea the Nelson compromise of a 5% above target student contribution cap would be much more workable than the hard, 0% margin of error, cap proposed in the Accord final report and this consultation paper.