For Australian higher education the situation of international students in the COVID-19 crisis is especially concerning. They lack the local family and social security back-ups of domestic students. It leaves them particularly vulnerable as large parts of the student labour market collapse.

And if international students have to go home or cannot pay their fees, that is the most likely trigger for a broader higher education sector crisis. At best, thousands of higher education workers will lose their jobs. At worst, many universities will need government intervention to survive.

This morning the government issued a summary statement on the situation of international students during the COVID-19 disruption.

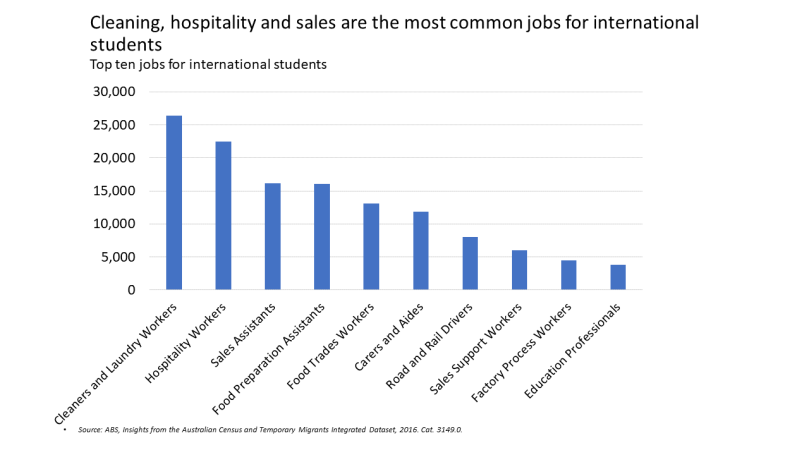

International students working in nursing and aged care have had their 40 hour per fortnight cap on working eased, as have students working in supermarkets until 1 May. While that is helpful for some students, as of 2016 the majority work in other occupations, as the chart below shows.

In its statement, the government makes the point that as a condition of their visa students must show that they can pay fees and living expenses for their first 12 months. Legally, that is a strong argument but it is probably an area in which visa applicants are not always entirely truthful. And most higher education students need to finance themselves for more than 12 months.

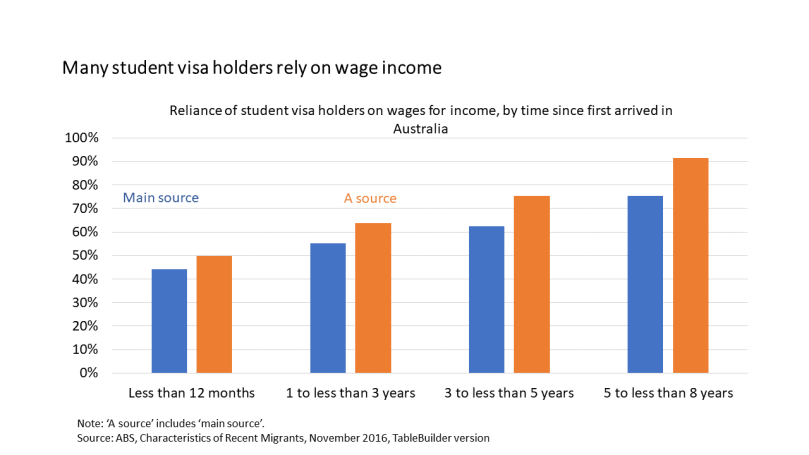

As the chart below shows, again using 2016 data, more than 40 per cent of international students who have been in Australia for less than 12 months report wages as their main source of income. The proportion relying on wages increases as they stay longer.

International students are also offered access to their superannuation. However, their work hours are restricted and mostly in low-pay occupations. Students won’t have much in their superannuation accounts. Exacerbating the problem, international students are particularly vulnerable to employers who ignore employment law. Superannuation contributions may never have been paid.

As Peter Mares has long argued, Australia has created a large population – nearly 1.8 million, at last count – of long-term but temporary visa holders without properly thinking though the social, economic or political consequences.

What happens to temporary migrants in a major crisis is one of the issues that needs a policy, especially when it will not be easy for many of them, as the prime minster suggested yesterday, to go home.

The general principle of reciprocity in the Australian welfare state is a reasonable one, so that the right to draw on benefits is linked to paying or being likely to pay taxes over a long period of time. Given that, it is fair to ask temporary migrants to arrive prepared for foreseeable costs and risks, such as the requirement to have health insurance.

But major adverse events that temporary migrants can neither predict nor control are in another category. To me, protecting them in such circumstances is one of the risks Australia takes on as a community in order to get the benefits of temporary migrants. We already do this in some ways; when the police or fire brigade are called nobody checks your citizenship status. These rights to assistance apply in narrowly-defined circumstances and for limited periods, as with the COVID-19 crisis.

Social security benefits aside, it is not clear why international students and other temporary migrants should be excluded from the JobKeeper payment. This policy is as much about business continuity as personal welfare:

The JobKeeper Payment will support employers to maintain their connection to their employees. These connections will enable business to reactivate their operations quickly – without having to rehire staff – when the crisis is over.

The visa status of a worker has nothing to do with how necessary they are for a business to re-start after the COVID-19 crisis is over. The policy could have very odd results. The 2016 ABS recent migrant survey found that the accommodation and food services industry, already devastated by a government decision to largely close them down, is the most reliant on temporary migrants (more than 9 per cent of all staff).

Indian and Chinese restaurants might find themselves with many ineligible employees, while restaurants serving cuisines less linked to recent migrant countries of origin will have more eligible staff. It seems arbitrary and unfair for the businesses and their customers as well as the temporary migrant staff.

Apart from health considerations, the most important aspect of public policy right now is minimising the number of organisations that collapse due to the COVID-19 shutdown and recession. More flexibility on how temporary migrants are treated during the COVID-19 crisis would help with that goal.* It would reduce the risk of disaster in the higher education sector, as well as in the many small businesses that rely on temporary migrant workers.

——————————————–

* While sounding well short of what is needed, today’s statement did also say that ‘the Government will undertake further engagement with the international education sector who already provide some financial support for international students facing hardship.’

This is a beautifully constructed post, dense with great links. Any reciprocal bargain in contingent visas that allow and to a large extent depend on work certainly has been suspended here. It will be fascinating to trace any permanent effects on demand for student visas.

LikeLike

One might also add that if international students and temporary workers are left high and dry, word will soon get around their networks overseas about how Australia treated them when the crunch came. That, in turn, could tend to discourage people from seeking to study or work here in future. And that could be particularly damaging in relation to higher education, where Australia could, if it plays its card right, attract the best and the brightest of the international market for a few years: people who, seeing how badly the coronavirus has been handled in Europe, the UK and the USA, would prefer to come to a country which has its act together

LikeLike

As a local student studying at the University of Melbourne I think that there are stronger economic reasons as to why international students may not choose to study in Australia. As Andrew would later write in this article https://andrewnorton.net.au/2020/06/01/why-did-universities-become-reliant-on-international-students-part-1-government-funding-cuts/ a higher Australian dollar compared to our competing countries, UK and USA would have more of a negative effect.

I was employed at the MCG with Spotless and conversations with Colombian and Indian students reveal that the reason they choose Australia over the UK is because in the UK they enforce that students can work no more than 20 hours a week. Whilst we have that law it is not policed with the same vigour in the UK.

Furthermore, as Dr Pulla notes below, many students come here because their families raise the funds to send their children here. The government stipulates that you must have 12 months worth of savings in your bank account before you commence your life as a student here. However, discussions with my Colombian colleagues indicates that once they arrive here those monies have to be returned to various family members. Essentially they are buying a product they can not afford. If I buy a car and can’t afford the conditions of the load the bank would reposess my car and I would be left with a bad credit rating. Likewise, if an international student can’t satisfy the conditions of their inital contract with the Australian government, why should the government turn around and bail them out?

There maybe some negative network effects that take place because the government hasn’t provided on-going financial support for international students, however neither have our competing countries. (USA and UK)

As I point out to my colleages from Colombia, the situation is the same for international students studying in Colombia – no government handout so why should we give one?

LikeLike

Thanks for picking up this area and strongly advocating for international students. A couple of months ago universities were looking at different options of even hoteling in a couple of countries before they could bring back non-Covid – uncompromised Chinese students – but today we have the second largest group that is the Indian students- most of them that come from middle income households- ( middle incomes in India not comparable to lower Australian taxation bracket) Many of them come here- by borrowing from banks etc. Additionally, we also have dubious agents on both soils- that add to the calamity.

Irrespective of the quality of the student each is an aspirant and I think we have a duty of care as a nation. Many that are in post graduate courses scrupulously study our man power forecasts for the future of Australia. Many of them have genuine desire to make Australia their home in future. using ethical and legal means. These are skilled here as per our systems and It would be a shame if they have to return to their countries on charity flights provided by the Indian High Commission. Mr Prime Minister, we appreciate what you do with our citizens. But it is also the time for you to tell the universities that the fat accrued from these ‘cash cows’- at least some of it be returned to the bleeding cows- Time for you to ask universities to pitch in.

Dr Venkat Pulla

LikeLike