The three politicians with the greatest impact on higher education participation were Robert Menzies, John Dawkins and Julia Gillard. Yet I never hear anyone say, depending on their age, that “I only went to university because of Menzies/Dawkins/Gillard”.

Yet for Gough Whitlam the story is different. Last week USQ VC Geraldine Mackenzie was reported in the Australian saying “I was very fortunate to go to university after the Whitlam years when it was all free. Otherwise I may not have had that same opportunity.” And in February shadow education minister Tanya Plibersek told the Universities Australia conference that “it feels like every week, I meet someone in their 60s or 70s who reminds me about how Gough Whitlam was responsible for them going to university.”

I have argued before that Whitlam, Prime Minister 1972-1975, was very significant in the history of Australian higher education and has some lasting legacies. But I think the lesson from Whitlam’s time for now is that the biggest drivers of participation are supply-side policies on student places, and in particular how they interact with demography and fiscal policy. Because both these factors were significant in the free education era, the long-term trend towards increased higher education participation was interrupted.

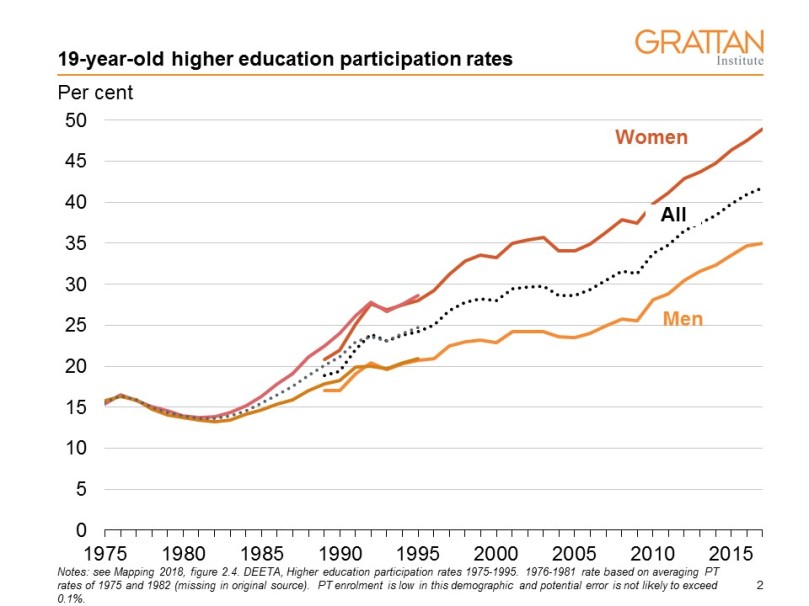

Free education lasted from 1974 to 1986 (there were small charges in 1987 and 1988, before HECS started in 1989). The chart below shows that 19-year-old participation rates went up in 1976 but then fell and did not return to the previous peak until 1986. At the low point in 1982, the 19-year old higher education participation rate was 2 percentage points lower than it had been in 1975 (unfortunately, my data source starts in 1975).

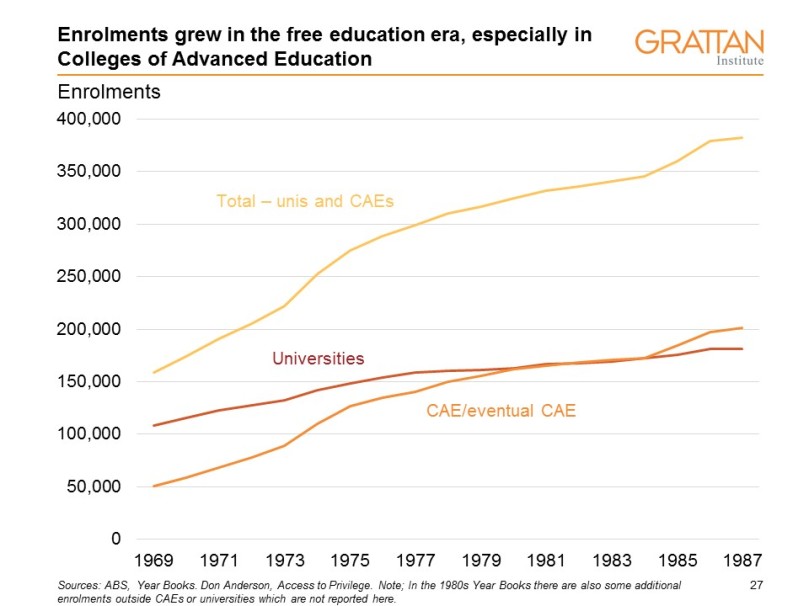

Enrolment statistics from the free education era are complicated, because teacher colleges were being brought into the college of advanced education system (which in turn became universities by the early 1990s). I have used teacher-college data from the ABS Year Books of the time to try to create a smoother time series than in the Department’s statistics. This data shows that enrolments were increasing, and therefore cannot be the cause of a declining participation rate (chart below).

Consistent with the Whitlam-as-opportunity-maker memory, 1974 was a year of exceptional higher education enrolment growth of 14 per cent across CAEs (23.5 per cent) and universities (7 per cent). This was an era of rapid enrolment growth. The CAEs had double-digit growth rates from 1970 to 1975. Both Whitlam and the Liberal governments on either side of him favoured the cheaper CAEs as the drivers of growth (“without Whitlam I would not have had the opportunity to go to a CAE” does not have quite the same ring to it, but historically it is more likely to be true than the same claim about going to university).

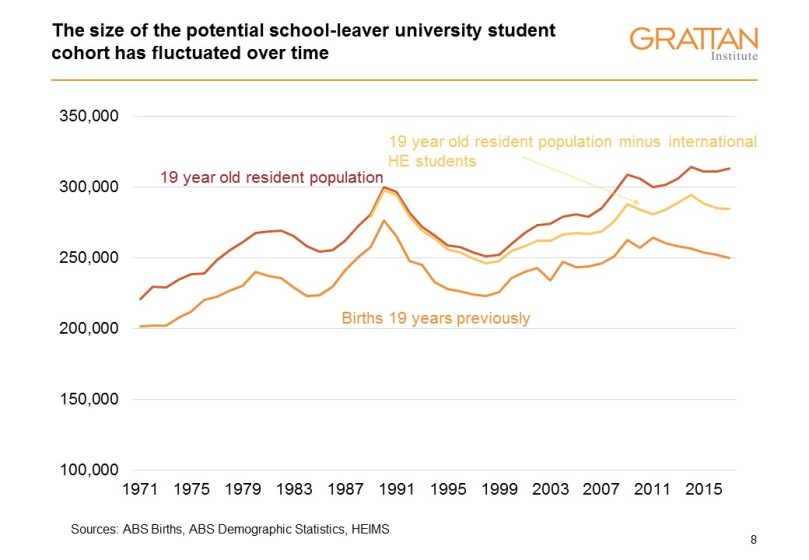

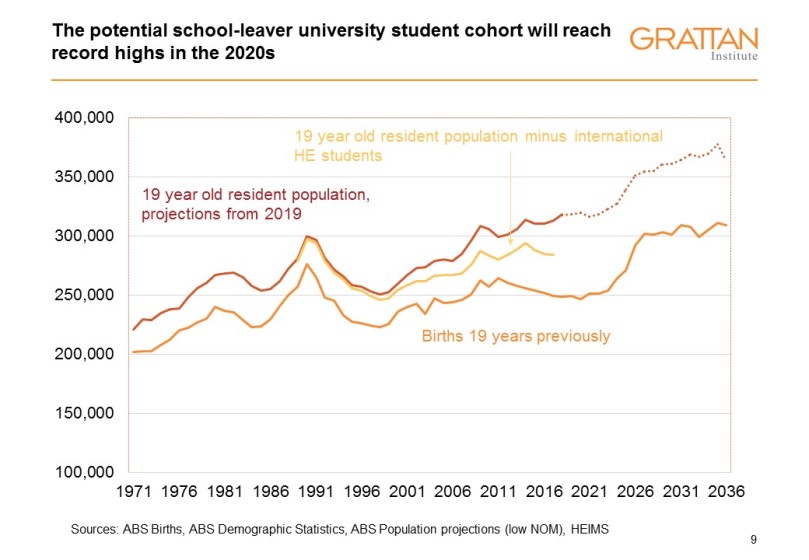

While enrolments were growing, so was the population. In the 1970s the children of the post-war baby boom era were reaching university age (chart below). Migration had an impact too, with the resident late-teenage population being much larger than can be explained by births. While the potential higher education student pool was limited by school retention rates to Year 12 , which had increased only slightly to around 35 per cent in the late 1970s, the larger population meant more people were seeking further education.

The low participation result in the early 1980s was because these were peak years for the main school-leaver age group who would be looking for higher education. The number of student places was increasing, but not quickly enough to meet population growth. As the late teenage population started to decline in the 1980s, the participation rate went up again, assisted by stronger growth in student places.

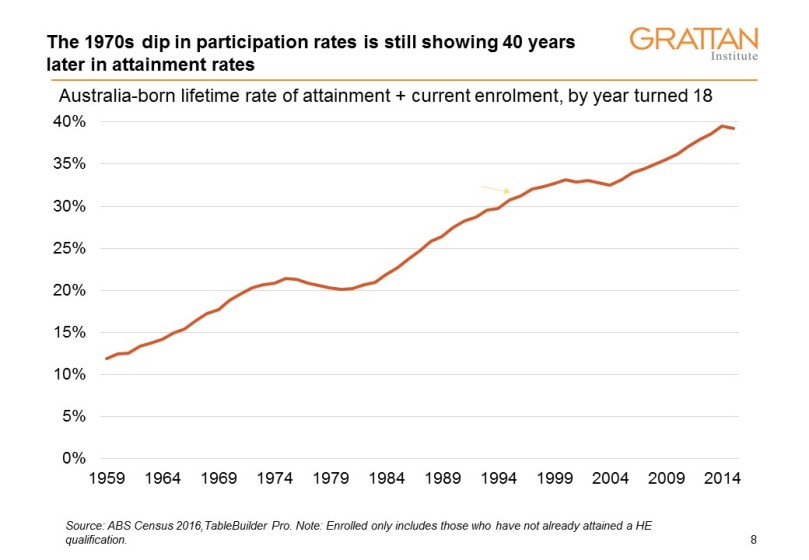

Mature-age study lets some people who missed out on higher education after school get a degree. But as the chart below shows, there are long-term effects of limited opportunities for school leavers – even 40 years on there is a dip in lifetime higher education attainment rates for Australia-born people who completed school in the late 1970s and early 1980s (for citizens it is a plateau at around 21 per cent; especially in recent decades migrants often arrive with a qualification, making citizen or resident attainment rates less reliable guides to how well Australia’s higher education system is going).

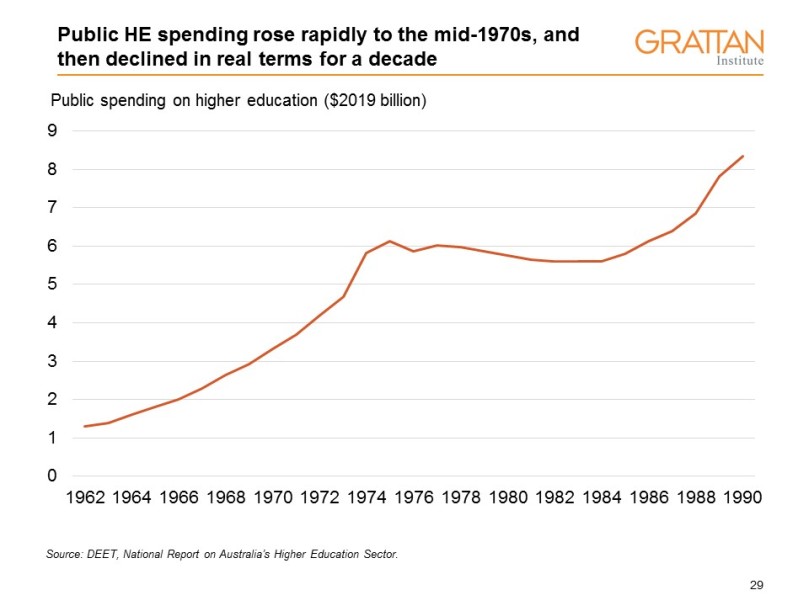

Given the demographic trends, averting a decline in higher education participation in the late 1970s would have required significantly increased expenditure on higher education. But in late 1975 the big-spending Whitlam government was replaced by the Liberal Fraser government, which was in office until 1983. Fraser was determined to reduce the Budget deficit. As a result, total higher education spending went into a decade-long period it which it was, in real terms, below the previous 1975 peak (chart below).

Given the demographic trends, averting a decline in higher education participation in the late 1970s would have required significantly increased expenditure on higher education. But in late 1975 the big-spending Whitlam government was replaced by the Liberal Fraser government, which was in office until 1983. Fraser was determined to reduce the Budget deficit. As a result, total higher education spending went into a decade-long period it which it was, in real terms, below the previous 1975 peak (chart below).

(As with the enrolment and lifetime attainment charts above, the public spending chart below shows that higher education was already in a long expansionary phase before Whitlam came to power, as Liberal governments continued with the expansionary policies of Robert Menzies, PM 1949-1966.)  For enrolled students, free education was not as radical a change at the time as it seems in hindsight. I can’t locate fee revenue in its last year, 1973, but in 1971 it was the equivalent of about $330 million in today’s money, compared to combined Commonwealth and State spending of $3.7 billion. Most people had scholarships or paid fees that were low by today’s standards. Replacing State spending of $1.6 billion was the more expensive transition cost to the new system.

For enrolled students, free education was not as radical a change at the time as it seems in hindsight. I can’t locate fee revenue in its last year, 1973, but in 1971 it was the equivalent of about $330 million in today’s money, compared to combined Commonwealth and State spending of $3.7 billion. Most people had scholarships or paid fees that were low by today’s standards. Replacing State spending of $1.6 billion was the more expensive transition cost to the new system.

Given the imbalances between State and Commonwealth taxing powers the Commonwealth takeover of higher education was, while not inevitable, not surprising either. But combined with the abolition of student fees it created a very tight link between university finances and the Commonwealth’s Budget situation. The risks of this rapidly became apparent in the subsequent decade of stagnation.

Although fees were not a large revenue source prior to 1974, their retention would probably have reduced the effects of public spending constraint. The introduction of HECS in 1989 (by John Dawkins, in the Hawke-Keating Labor government of 1983-1996) helped finance a large increase in total spending, enrolments, participation and attainment. With a spike in the late teenage population at the time participation rates would have plunged without strong policy action.

Like the Fraser government had 20 years before, the Howard Liberal government (1996-2007) in the mid-1990s cut public higher education expenditure to reduce the Budget deficit. Although the Howard cuts were much bigger than Fraser’s, the higher education participation rate kept growing under Howard. This was because most of the cuts came from reducing direct grants and increasing HECS by a corresponding amount, and because the school leaver cohort had declined since the early 1990s. For the participation rate, demography helped offset the consequences of deficits.

Over the long run, Australian history and global experience suggest that neither demography nor deficits will stop the rise of higher education participation. If we look at the lifetime attainment chart at decade intervals, the trend is always towards higher rates of attainment. Eventually the social and political pressure to provide university education leads to policy change. But over the short to medium term, demography and deficits do make a difference to educational prospects.

This is where the differences between demand driven funding (2012-2017, announced by Julia Gillard as education minister in 2009 and starting while she was PM 2010-2013) and block grants (all other years) become interesting. With block grants, the default main driver is the Budget. Apart from indexation, under block grants a significant expenditure increase requires a Budget decision, a trip to the expenditure review committee where it must compete with all the other demands on a limited revenue base. Unsurprisingly, when there are deficits the answer to a request for more money for higher education is often “no”, “not much”, or “take a cut”.

With demand driven funding, the default main driver is demography. If there are more young people then demand will go up and student places will grow to meet the demand. Stopping spending, rather than increasing spending, is what needs a major decision that has to go through the government’s internal processes. Eventually that decision was made at the end of 2017, and there had been cuts to other higher education programs along the way. But especially over the 2009 to 2014 period we had both significant large year-after-year publicly-funded enrolment growth and Budget deficits, two things that had not coincided over the previous 40 years.

We are now in a demographic lull, so the current funding freeze is not likely to cause participation rates to go down much if at all. Turnbull/Morrison have the luck of Howard rather than Fraser. But this will change in the 2020s, as the chart below shows. The rise of temporary migration makes it hard to know exactly how large the late-teenage population entitled to a Commonwealth supported higher place will be. But with the relevant birth cohort exceeding its previous peak and large numbers of migrants gaining permanent residence over the last decade, demand for higher education is likely to reach record levels.

Labor has promised to restore the demand driven system in 2020 if it wins the 18 May election. This is good news for Tanya Plibersek. Otherwise she could end up like Gough Whitlam, who had grand visions but created policy structures that weren’t robust to the challenges of demography and deficits.

[…] medium to long run, however, current policies would cause significant problems. In the mid-2020s, Australia’s school-leaver population will be larger than at any time in our history. And a shrinking higher education system would be […]

LikeLike

So much writing, so little message.

The only interesting thing is that 50% of females got to uni but only 35% of men do – hmm, so let’s through more money and help at women’s education – cause god knows that they need it.

But it does make you wonder why they (the elites) keep pushing for $ in women’s education. Me humbly thinks it’s a misguided attempt to barrow the wage gap – that is, uni degrees people earn more, so let’s get more women into education.

But alas, they confuse causation with correlation. The wage gap ain’t ever gonna narrow – so give it up !

University is such complete BS – waste of time

LikeLike

[…] important to note, however, that higher education participation rates have been trending up in Australia and around the world for decades, despite significant differences in funding policies. Demand […]

LikeLike